In 2013 Sugata Mitra spoke at TED about building a school in the cloud, a wonderful idea (even at the time of coronavirus) and a good talk for #LearnFromTED.

As it is with this series we see presentations that are both interesting for the topic and for the public speaking skills we can observe. So watch the video and then I am to highlight some points.

The opening immediately catches the public attention with the oldest (and best) trick in the book: storytelling. And Mitra is explicit about it. It’s a good idea before telling a story to let the audience know about it, to grasp their focus.

I do have a plan, but in order for me to tell you what that plan is, I need to tell you a little story, which kind of sets the stage.

And then the story follows.

I tried to look at where did the kind of learning we do in schools, where did it come from? And you can look far back into the past, but if you look at present-day schooling the way it is, it’s quite easy to figure out where it came from. It came from about 300 years ago, and it came from the last and the biggest of the empires on this planet. [“The British Empire”] Imagine trying to run the show, trying to run the entire planet, without computers, without telephones, with data handwritten on pieces of paper, and traveling by ships. But the Victorians actually did it. What they did was amazing. They created a global computer made up of people. It’s still with us today. It’s called the bureaucratic administrative machine. In order to have that machine running, you need lots and lots of people. They made another machine to produce those people: the school. The schools would produce the people who would then become parts of the bureaucratic administrative machine. They must be identical to each other. They must know three things: They must have good handwriting, because the data is handwritten; they must be able to read; and they must be able to do multiplication, division, addition and subtraction in their head. They must be so identical that you could pick one up from New Zealand and ship them to Canada and he would be instantly functional. The Victorians were great engineers. They engineered a system that was so robust that it’s still with us today, continuously producing identical people for a machine that no longer exists. The empire is gone, so what are we doing with that design that produces these identical people, and what are we going to do next if we ever are going to do anything else with it?

Have you noticed the language used? The emphasis brought by the last and the biggest of the empires on this planet or trying to run the entire planet. Don’t be afraid to be bold with your language, use evocative images that can raise powerful images (and emotions) in your audience.

You also probably noticed two other things, a subtle ironic humour, and the contrast between a great machine… that is not useless. Logical contrast is again something that is vivid and keep people’s mind very active, therefore more ready to receive your message. The slides you saw in the video helps too.

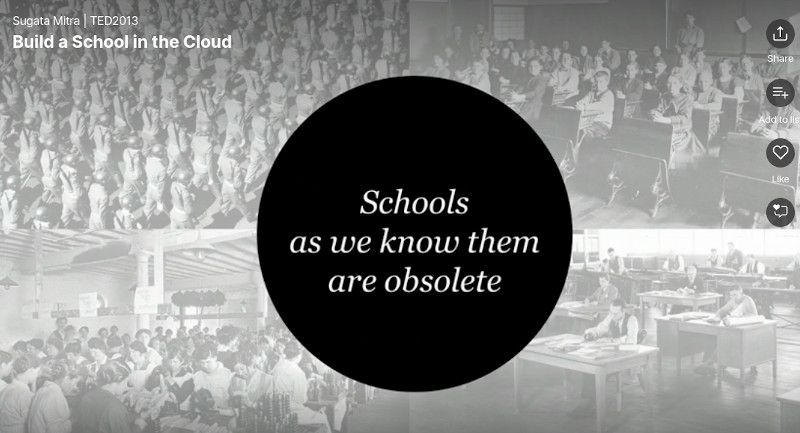

All of this story accomplish one task: convey this message.

How more powerful is to use that story, and that parallel, that simply state it and support it with logical facts?

Now some in the audience may object in their minds: “Another one that says that the school system is broken…”. Mitra addresses it upfront.

So that’s a pretty strong comment there. I said schools as we know them now, they’re obsolete. I’m not saying they’re broken. It’s quite fashionable to say that the education system’s broken. It’s not broken. It’s wonderfully constructed. It’s just that we don’t need it anymore. It’s outdated.

This is helping him getting more attention and credibility from possible sceptical people. What maybe your audience doubtful about? How can you acknowledge it while making your point?

Humour is another great technique to keep the audience engaged, focused (laughing is breathing for the brain) and listening. Here are some passages.

At the same time, we also had lots of parents, rich people, who had computers, and who used to tell me, “You know, my son, I think he’s gifted, because he does wonderful things with computers. And my daughter — oh, surely she is extra-intelligent.” And so on. So I suddenly figured that, how come all the rich people are having these extraordinarily gifted children?

I went 300 miles out of Delhi into a really remote village where the chances of a passing software development engineer was very little.

When they saw me, they said, “We want a faster processor and a better mouse.”

In an irritated voice, they said, “You’ve given us a machine that works only in English, so we had to teach ourselves English in order to use it.”

So a little girl who you see just now, she raised her hand, and she says to me in broken Tamil and English, she said, “Well, apart from the fact that improper replication of the DNA molecule causes disease, we haven’t understood anything else.”

I know more British grandmothers than anyone in the universe.

In the body of the presentation Sugata Mitra shows lots of videos about the children, learning, interacting with the computer and so on. Do you like them? Do you think they support visualising ideas for the audience? How can you implement videos in your presentation or when you are speaking before a group?

The central section has also some technical aspects, and that’s the best place where to put them. The brilliant opening got everyone enthralled and so they will keep their attention also for the serious part. That section doesn’t hinder, on the contrary, it adds credibility because it creates the right mix between providing entertaining stories (fully contextual) and supporting evidence.

When it’s time to make his point, that comes very clear, and so you should do. Be bold, be clear, make it easy for the public to understand the message you want them to bring home.

So what’s my wish? My wish is that we design the future of learning. We don’t want to be spare parts for a great human computer, do we? So we need to design a future for learning. And I’ve got to — hang on, I’ve got to get this wording exactly right, because, you know, it’s very important. My wish is to help design a future of learning by supporting children all over the world to tap into their wonder and their ability to work together. Help me build this school. It will be called the School in the Cloud.

(…)

But I want you for another purpose. You can do Self-Organized Learning Environments at home, in the school, outside of school, in clubs. It’s very easy to do. There’s a great document produced by TED which tells you how to do it. If you would please, please do it across all five continents and send me the data, then I’ll put it all together, move it into the School of Clouds, and create the future of learning. That’s my wish.

Going towards the end of the talk there’s another beautiful story.

And just one last thing. I’ll take you to the top of the Himalayas. At 12,000 feet, where the air is thin, I once built two Hole in the Wall computers, and the children flocked there. And there was this little girl who was following me around.

The picture of the girl and what she says is the icing on the cake. A piece of advice we can add to the rest we have just seen in this talk.

I wish Sugata Mitra can achieve his School in the cloud and you can achieve your public speaking objectives (also by learning from him)!

Recent Comments